| | ||||||||||||||||||

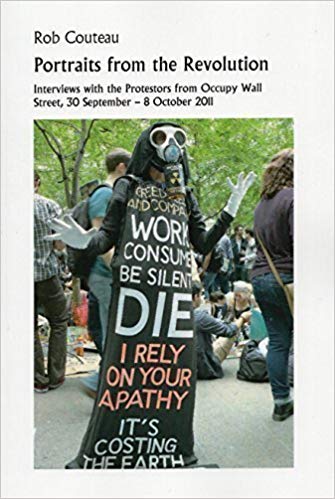

| At the northeastern edge of the Liberty Square, I encountered a youthful-looking man in his early forties who was sitting on the ground, handing out flyers advertising his book. When I read the title, Troublemakers: Power, Representation, and the Fiction of the Mass Worker, I sat down and conducted this impromptu literary interview. William Scott is an associate professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh. He's been sleeping at Liberty Square since he first arrived, on October 6. A few days after our talk, he started to work at the "People's Library" as a volunteer. Troublemakers, published by Rutgers University Press, is his first book. Rob Couteau: Whatís your book about? William Scott: Itís about the way novelists portrayed mass-worker movements in the first half of the twentieth century. When I say mass workers, I mean workers in mass-production industries, like auto, steel, that kind of thing: on assembly lines.

In part, itís about a new form of power that mass workers discovered they had: one that did not depend on union representation or political party representation. It was a power they derived not so much through a power of numbers but through their position at the workplace, on the assembly line. That is, when ten workers discovered that if they stopped work they could shut down a whole factory if they sat down, that was an enormous power that workers discovered. This new form of power created a crisis for novelists who tried to represent mass-worker movements. Because what they were trying to do was to show that mass workers in their oppressed conditions on assembly lines actually did have a form of power that was not the conventional form that was popular in the nineteenth century Ė power through representation, power through political parties in unions Ė but, rather, that they had a kind of structural or material power from the workplace itself. And so, my book is about how novelists represented this new kind of worker and this new form of power. I talk about novels that tried to detail sit-down strikes, or acts of spontaneous sabotage, or, in general, direct action: direct democracy movements in mass-industrial settings. RC: How long have you been teaching? WS: For about eight years. I was at New Mexico University at Las Cruces for about two years, in the English department there. Iíve been at Pittsburgh for six years. RC: How long did you work on the book? WS: On and off, for about ten years now. The basic idea at the core of my doctoral dissertation is about leftist writers in the Great Depression in the U.S. I wanted to expand the scope of that but to keep the basic argument. RC: So, this grew out of your dissertation. WS: Grew out of it, but itís a separate book from the dissertation. RC: Who are the writers that you focus on? What's the main group?

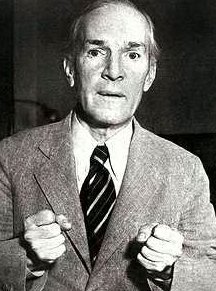

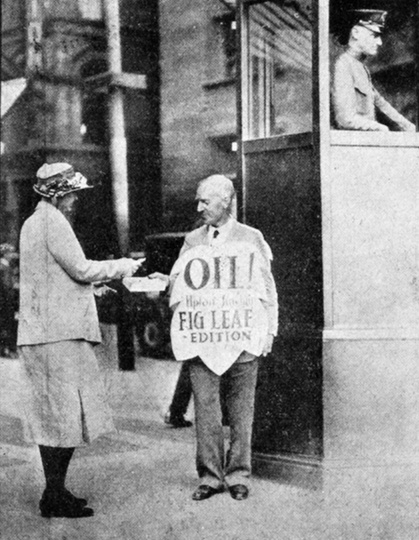

WS: Maybe the most well known writers that I discuss in the book are people like Upton Sinclair; Jack London, a little bit; Dalton Trumbo: these are some of the better-known writers. The rest of them have fallen into obscurity. At the time their books were initially published, though, many of them were bestsellers. Some of the novels that I talk about from the progressive era Ė that is, from the period of World War I Ė were bestsellers and were well known but have fallen into obscurity since then. One of the purposes of the book is to revive attention to these forgotten novels. RC: You mentioned Dalton Trumbo Ö WS: Dalton Trumboís novel, Johnny Got His Gun, was a controversial and famous antiwar novel from 1939, and I talk about that in the book. RC: I forgive myself for not recognizing his name at first, because thatís one of those situations where the book title is more famous than the authorís name. WS: It is. I think they made of film of it, as well.* RC: My father gave me that book when I was about fifteen years old, and we were just discussing it the other day. Itís an amazing work: probably, one of the first antiwar novels to come out of the United States. WS: You could say The Red Badge of Courage, by Steven Crane, a book about the Civil War, could count as an antiwar book. Itís considered a strong antiwar statement. RC: Yes, thatís true. Johnny Got His Gun is certainly the first American novel to come out against the First World War. WS: Yes, exactly. It was a very popular book used for a sort of peace propaganda: an antiwar, pacifist propaganda novel. RC: Maybe you could mention some of the authors and books that have fallen into obscurity that youíre trying to highlight.

WS: One terrific novel from 1939 thatís out of print is by a woman named Ruth McKenney. Itís about the Akron rubber workers, the tire workers, and their sit-down strikes in the 1930s. Cornell University Press reprinted it in the early '90s, but itís been out of print for about twenty years. I would love to see that book put out again. Itís a fantastic novel. I have a lot to say about it. Then thereís Thomas Bell, author of a novel called Out of This Furnace, which is actually well known in Pennsylvania and around the Pittsburgh region. Itís about the Pittsburgh Steel workers. Thatís still in print, but itís not very well known. Then there are a bunch of novels from the progressive era, writers who were affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World: Leroy Scott, author of The Walking Delegate; another book by a guy named Ernest Poole called The Harbor, about a dock workers and harbor workers in the New York harbor. A wonderful book. Then a book by a guy named Arthur Bullard called Comrade Yetta, from 1913, about textile workers in New York: shirtwaist workers, and that kind of stuff. So, these are a few of them. The list goes on, and there are other novels that I could mention. RC: How did the idea for this generate? Where did you get the idea? WS: As I said, my doctoral dissertation and my research was about leftist writers from the Great Depression, and, in the course of doing that research, I discovered there was a broader tradition of radical literature in this country. So I wanted to do something that would be broader than just a focus on the 1930s. Thatís pretty much the origin of it.

RC: What gave you the idea of doing the dissertation originally? WS: When I was in graduate school, I was interested in the history of U.S. social movements. I was in a comparative literature program, so I started off studying German literature and German philosophy: that sort of thing. Then I discovered there was a movement of radical writers, leftist writers, in the Depression. I had no idea who these authors were. The only writers I ever knew from the 1930s were people like Hemingway, Steinbeck, Grapes of Wrath. But to learn that there was a whole movement that was organized, and they had conferences, journals, magazines, and they published all sorts of stories, poems, plays, and novels from this era: that just blew my mind. So, I decided I wanted to learn more about it and that it would be a good topic: an under-researched field that needed to be looked at again. RC: You discuss major writers such as Upton Sinclair, whom we all think of as exploring this theme as a focal point of their novelistic creations. But do you also mention writers whom we donít necessarily associate with that theme but who were, nonetheless, affected by it and who dramatized it to some extent? WS: Pretty much all the writers I write about were writers who had a commitment to writing about class issues and about the situation of the working class. So, itís hard for me to think of writers who took up that intent as a sort of peripheral or secondary kind of thing. John Steinbeck would be a good example. I donít write about him in the book. But heís a good example of someone who has a sort of side interest in workers movements in this country, and he addressed it in some of his novels. Grapes of Wrath is the most famous one. Maybe Dalton Trumbo is the most famous example of somebody. Johnny Got His Gun is not typically thought of as a book about workers. But in the novel, itís clear that the main character is there to be a typical example of a modern mass-industrial worker. Jack London is another writer who was personally a socialist and was involved with the Socialist Party. He didnít write a lot about workers, though, except in a few of his books. Maybe heís another good example of somebody like that.

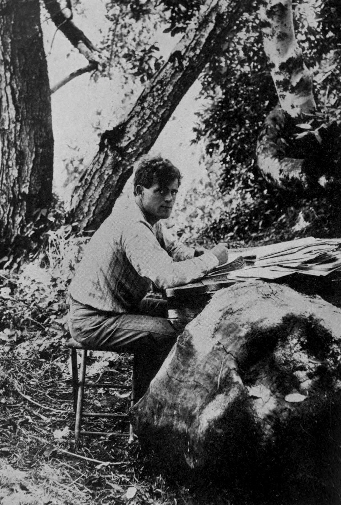

RC: Jack London brings a lot of those issues to the fore in his quasi-autobiographical novel, Martin Eden. WS: Oh, Martin Eden! Absolutely! RC: Thatís an amazing book, isnít it? WS: Yes! I donít write about it in my book; I write about The Iron Heel a little bit, which was a very popular book. And Martin Eden was too; they were both popular books with progressives and with labor activists in the progressive era. For example, he was one of the favorite authors of the Wobblies: the IWW. In many ways, Iron Heel was a prophetic book. Itís a fantastic novel. RC: You could also say that many of his tales and stories that have to do with going to exotic places, such as Alaska for the Gold Rush, are about people who are working, trying to make money. WS: Absolutely. Then there are his allegorical stories, as well. Even the tales about animals are often allegorical stories about human society. Historians and sociologists will tell you that this era weíre living in now, of big corporate capital, most resembles the period of the 1890s in America: the Gilded Age and the creation of monopoly capital. Big trusts, and things like this. Itís the kind of capitalism that Jack London was trying to describe in his books. For that reason, I think heís a very contemporary writer, and the things he says are relevant to many of the struggles that people are having today. RC: I recently interviewed Justin Kaplan, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography on Mark Twain. We were talking about Twain, Whitman, and the Gilded Age, and we touched on the fact that, yes, there really is a connection from that period to this period. Especially when I read about Whitmanís life, I see some amazing connections. The 1850s was a decade that you could compare to the 1960s: a time of eccentric personal fashion, culture, and, going all the way to the 1890s, disgust with the growing power of corporations and how the law was no longer equally applied between a citizen and a plutocrat. WB: Yes.

RC: Itís important that you brought that up, because thereís certainly a parallel. Which leads us to the fact that there are cycles that we see throughout history, and throughout American history. WS: Oh, yes, thatís true. In part, one of the reasons there are cycles is because, relatively speaking, Americans are less history conscious as compared with people in Europe, for example. I studied in Germany; I lived there for a while, and I followed the German news. One common feature of news stories there is the historical memorial days, or historical dates and things that echo back to certain aspects of German history, say, of the last hundred years. When they have these milestones, these anniversaries, these are major news stories. We never see that in our news here. You can grow up watching the news, if you even watch the news in this country, and never learn about American history. In this country, the news focuses on the present. In general, with Americans, part of their identity is to be always forward looking: gazing into the future and not looking back. This goes part and parcel with the ideology of American identity. RC: Thereís a reason for that, because this country attracted immigrants from other places. WB: Exactly. RC: At that time, in the nineteenth century, to take a big boat trip like that, you certainly had to have a lot of optimism about the future. You had to be a gambler; you had to be a bit of an intuitive: to believe in possibilities rather than actualities. WB: Right. RC: Thatís the filter through which the American character has been formed. WS: Yes, absolutely. I think for this reason, too, though, the downside is that we do tend to repeat things. In part, there are cycles because of this almost constitutional amnesia. RC: We forget about the past.

WB: We forget about the past, and then the past repeats itself. Vietnam is a wonderful example, a timely example. Iím a big fan of the history of the Vietnam War; Iím very interested in it. Iím fascinated by the ways that it was debated, the ways it was resisted: all those kinds of things. Also by the rationale, the motivation that was used to get us in the war and to keep us in the war for all that time. If you look at the arguments that were made, and the mission of the U.S. military in Vietnam, almost point for point, it matches up with Afghanistan. Not so much with Iraq, but with Afghanistan. That is, you have a mountainous region, nomadic peoples, and our mission there is to spread not just democracy but to spread a kind of service: a ďgoodwillĒ mission, right? But itís a war, nonetheless. When you hear pundits denying the similarities between Vietnam and Afghanistan, I think they have to do that to distract attention away from the glaring parallels and similarities. I grew up watching movies like The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now: all these movies that were critical of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. And I grew up naively thinking, well, with films like this, weíll never have to worry about another Vietnam, because everyone knows why itís wrong and whatís wrong with these kinds of wars. With any war, but with these in particular. Yet, it started all over again, ten years ago. RC: The powers-that-be have a great interest in dumbing down the Americans, and in underfunding education, because they donít want people to know about these things. WB: Right. RC: One of the big differences between Vietnam and Afghanistan is that they learned their lesson after allowing the journalists roam free through the jungles of Vietnam. In Iraq and Afghanistan, they created a policy of so-called embedded journalists: reporters were attached to military units and couldnít wander around, unsupervised. Another difference is that it became unlawful for journalists to photograph the coffins coming back, draped in American flags. WB: From Afghanistan and Iraq, yes.

RC: Thereís even more control of the media now than there was back then. I grew up in the 1960s, watching the TV every night at the dinner table Ö WS: The dead bodies Ö RC: Yes. During the news, wherever you were in America, youíd see the names of the boys, often from local neighborhoods, who were killed, and where they were from. Largely, these were body bags that came back to the middle class. And because the middle class was affected, thatís what galvanized the antiwar movement and made it a serious threat to the status quo. The connection between those protests and this one - which weíre sitting in the midst of today - is that the middle class are a majority of the ninety-nine percent. Theyíre directly affected, even though, now, the issue is the economy. WS: Yes, I totally agree. The other day, there was a woman at the general assembly meeting who was saying that the thing this generation, and this particular protest, has in common with the antiwar protests in the í60s is that, in the í60s, everyone was worried about being drafted. You stayed in college so you wouldnít get drafted. And the way to protest this was to burn your draft card. Everyone knew that they were at risk for dying; they knew people who were dying, they knew they, themselves, were at risk for being sent over there. It was also clear that it was a war against lower-income Americans and people of color. They were the vast majority of the people who were being put on front lines and being killed. RC: Especially by 1968, toward the end of the war. WS: Exactly. We donít have a draft today, and the thing about the war in Iraq and in Afghanistan is that the majority of middleclass Americans donít feel directly affected by that. They donít feel as though theyíre at risk for being sent over and killed. However, what we do have today, which students did not have in the í60s, is student loan debt. And the easy availability of credit has made it even worse.

When I was an undergraduate at SUNY Buffalo, during my first year on campus, credit companies literally gave me credit cards and said, ďHere, go out and use this.Ē I didnít even have to apply. They literally gave them to me on the spot, on campus. They had tables set up, and they were handing out credit cards. So, what did I do? I was like, ďHey, Iíve never had a credit card before. Iíll go and buy some CDs.Ē I go and buy some CDs; Iím into debt immediately. This is twenty years ago. Ever since then, Iíve been struggling with paying off credit card debt, student loan debt. I had to pay for my own tuition through college, so I had to take out student loans. Iím still paying that off. Thank God, I have a stable job, a good job, and I can pay it off. But the situation that this puts the vast majority of people in, younger people especially, is that now, when youíre in college, youíre racking up debt. So, college is actually not a safe place to be anymore; itís the dangerous thing. And when people graduate with $100,000 in student loans, they have to take that job at Starbucks, and they have to take that job willingly and obediently. They cannot talk back to their supervisors, because they need to keep the job to pay off debt. If they donít, then their credit is going to be screwed up, and their lives are going to be screwed up from that point on, and they wonít be able to buy a car or a house. So, this is an interesting parallel. What that woman was asking students to do was to burn their student loan paperwork. Which, idealistically, sounds wonderful. But, realistically, youíre screwing yourself if you do that. I would never have thought to do that myself. But itís true that if every student from today to tomorrow decided to not pay their student loans anymore, and to walk away from it, that would create another kind of crisis. RC: It may not be the most pragmatic solution, but itís a highly effective and dramatic symbolic action, which is very important to have in a movement. I often think of how, in 1967, Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies, and Allen Ginsberg, and so many other groups went down to Washington with the intention of levitating the Pentagon through yoga meditation and by chanting, ďOut, demon, out!Ē The Pentagon building is shaped like a five-pointed star, so they thought it was akin to a black-magic pentagram. [Laughs] And this event still resonates among contemporary historians of this period. Norman Mailerís book, The Armies of the Night, is about that same protest. So, these symbolic acts are very important. Burning a draft card is an image that resonates, that stays in peopleís minds, which people back then would have seen in Life magazine. Itís a provocation, an important provocation.

WS: Absolutely, I agree. If you want to see a parallel between this kind of action and that Pentagon action, youíre right to see it in these protests as well. Although, in some ways, the focus of the energy at this event, and at similar events that are happening around the country and springing up spontaneously in different cities, has a kind of focus, in spite of the fact that there are no clear demands or concrete sound-bite demands. The focus on finance capital is something that is extremely powerful and that was missing from the í60s generation, which was mainly an antiwar protest. To some degree, there was a critique of capitalism in there, as well. The problem in the í60s was that there were competing leftist ideologies. You had Maoists fighting with communists and this kind of thing. We were still in a cold war period, so communism became a banner under which people were organized, but it was a controversial one. Whatís great about this event is that itís relatively free from limited political or ideological definitions or categories. This is really a bonus. Yet, it doesnít lose its main focus on finance capitalism, on corporate capitalism. RC: Personally, why are you here today? WS: I have a sabbatical this semester; I donít have to teach. When I first started hearing about this, I thought: This is really important; I want to support it. Luckily, I donít have to teach classes now, so Iím here supporting it. RC: Considering what your book is about, this is the perfect question to ask you. Iíve brought this up a number of times with some of the younger people here. In the í60s and early í70s, unions never aligned with students. WS: Right. RC: A few blocks from this location, an event happened in the early 1970s that was photographed and widely reproduced. Construction workers attacked the youth movement as they were marching in protest: violently attacked them, beat them to a pulp. And now weíve got major unions, such as the U.S. Steelworkers and the Transit Workers Union, joining a largely youthful protest movement at the beginning: after just a few weeks. Whatís the significance of that to you? WS: That is huge. That is actually the secret of May 1968 in Paris. A short-lived kind of success, but, nevertheless, a significant coalition. This is what we didnít have in the U.S. in í68. Instead, there was a lot of tension between organized labor and the antiwar movement.

Thatís a complicated issue, which has a lot of factors involved in explaining why that is so. It took forty years for organized labor to realize they were getting shafted. In the í60s, that process had just started; it hadnít yet kicked in. Mass workers and unions were incredibly strong, and still had a lot to gain. The industrialization and outsourcing and all that stuff had not yet really hit home to industrial workers in this country. Forty years later, itís hit home in a major way. Weíve seen the outsourcing and export of an industrial economy out of this country. So, for many years, unions have been in the doldrums and have, in some ways, needed something like this to give them the sort of push they needed to speak out about it. RC: Itís easy to understand why, in May '68, the unions in Paris had an almost instant solidarity with the students, because thereís more of a history of that kind of thing there. When thereís a strike in France, it often leads to a domino effect. WS: Yes. RC: Why do you think it took so long for workers here to understand the need to create this coalition? Why do you think they attacked the students then, and theyíre not doing it now? Whatís changed? WS: I think itís because, in the history of our country and of our culture, the work ethic is extremely important. In the U.S., we live in culture that worships work for its own sake and that worships work for the sake of upward mobility. The American dream is about working hard and moving up. But thereís also a religious element to it: a Puritanical work ethic. To be a good American, you have to work hard. The tension between the student movement and labor existed throughout the 1960s. Hippies were called ďbums.Ē They were ďlazy bums,Ē and supposedly they didnít work. And so what hippy stood for was an antiwork ethic. This made them very unpopular with organized labor. The reason it took so long is because of the persistence and resilience of the work ethic: this never goes away. Even among the Left and people who are sort of ďpro-working class,Ē thereís almost a fetishization of working for its own sake: the value of work.

What youíre seeing now among working people and organized labor is a convergence of frustration with the economy, with Wall Street, with Congress, and with the outsourcing of jobs. Itís a dovetailing of that frustration with the anxiety of the student generation, who canít find work and who need to find work to pay off student loan debt. These two things are coming together, and itís happening right now. Thatís one theory I would have to explain why, now, thereís a compatibility. And organized labor has finally woken up to realize that itís OK to be critical of the American work ethic in some ways. RC: Weíre a little older than many people in this crowd. Especially with the seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds that I speak to, they really believe in their hearts that something fundamental is going to change. But you and I know how deeply corrupt this country is, and all governments in the world are, and what a dark network exists between governments, major corporations, organized crime, international narcotraffickers: all of that. Thatís the real worldwide web if there is one. Bearing this in mind, where do you think this is going to go? Whereís it going to be a year from now? How are people going to look back on this, twenty or thirty years from now? Are these kids going to be disappointed when the fundamentals donít change? WS: Honestly, I canít tell yet. I would be uncomfortable making predictions about that. One side of me, the cynical side, sees all this getting burned out as soon as the weather gets cold and everyone goes home. Then itwill be a blip on the radar of the popular cultural history of the United States and nothing more. But another part of me, though, the less cynical and more optimistic and hopeful side, thinks that even if the momentum of this particular action trails away, others will take its place. That it will start a domino effect that we havenít seen in our country for a long time. That could be really positive. So, I donít know. A year from now, what I would love to see is for politicians to actually try to respond to these kinds of demands. Just in the last two years, youíve seen the political response, directly, to the Tea Party actions around the country. A very organized movement, and they were directly responded to. They had leverage in the last election, and they will have leverage in the next election. If a similar kind of thing from a progressive point of view could have the same kind of leverage, that could help to balance the scales a bit. Because in the direction the countryís been moving in the last few years, and particularly with the rise of the Tea Party, Iíve been really frightened, you know? When I hear the Republican nominees, itís really frightening, the kinds of things I hear them say, and the kind of things I know they would be supporting. So, if nothing else, even if this fizzled out next week, it could still have the potential to exert some influence in electoral politics.

A lot of people that youíll speak to here are against electoral politics completely. They think the whole system is completely corrupt. And thatís a valid position to have. Representational democracy is incredibly corrupt, especially when corporations are considered people and they can vote, and they can donate as much as they want to campaigns. This makes everyone here very skeptical. RC: Talk about a symbolically significant image Ė a corporation as a person! WS: Absolutely. That captures the essence of something that is so upsetting to people here. RC: In fact, corporations have become people because the governmentís allowed for it. I mean, they have become people in the sense of having personal rights. Even more than people: like ďsuperpeople.Ē WS: Yes. Thatís why I think itís valid for a lot of people here not to want to participate in electoral politics. Thatís fine, but if Sarah Palin is our next president because they didnít go out and vote, theyíll only have themselves to blame! So, I think itís right to critique the system of electoral representation and democracy, but you work with what youíve got. RC: I think the two things are important: voting, as well as taking to the streets. And right now, taking to the streets is a very important thing to do. WS: Yes. In this country a hundred years ago, there was a very similar debate about the value of electoral representation. The Socialist Party was pushing for Eugene Debs to get a lot of votes and to become president. Campaign after campaign, he kept running for president, and he kept getting more and more votes. Upton Sinclair talks about it in The Jungle. But there was another sphere of labor people and activists who said this was all a waste of time. The Industrial Workers of the World were competing against that system of democracy. They felt we needed a direct democracy or a workerís democracy. A direct democracy that would become a reality, through the direct action of workers. In many ways, the reason why this protest appeals to me so much, and interests me so much, is that I see this as a version of that. Just people realizing a new form of democracy. RC: What do you think the role of the writer Ė specifically, the fiction writer, the novelist Ė is in todayís society? Iím asking that question in this context: In the decades before television, even for people who werenít necessarily interested in literary things per se, there were often books in the house as a form of entertainment. But with the advent of television, the novel became less influential in the United States. One of the indications of this is that organizations such as the CIA spent less and less time, money, and energy on infiltrating literary magazines and literary groups, and on keeping tabs on authors, and stuff like that. Now it was the celebrities and film stars that were surveilled, because they had so much power. A movie star could call a press conference. For example, itís rumored that Marilyn Monroe was going to call a press conference on the Monday that would have followed her mysterious death, to talk about the Kennedys and how they double-crossed her.

In some interview, thereís an apt quote by Arthur Miller. Just before he was due to testify at the House Un-American Activities Committee, he received a message from the congressmen who was in charge of the hearings, who told Miller: If Marilyn Monroe would just pose in a photo with me, Iíd be willing to drop the whole thing. And Miller later said, This, to me, was like what we call the cathartic moment in a play: the emotional focal point in which everything is symbolized in one quintessential gesture. He said the significance of this was that they werenít calling lowly secretaries and bureaucrats from the American Communist Party to their hearings; they were calling Hollywood celebrities, because this was the only way to get headlines. This is a long, roundabout approach Iíve gone into, but bearing all that in mind, what is the political role of the novelist today: the type of novelist that youíre interested in? WS: I would hesitate to spell out particular criteria for things that writers ought to be writing about, or anything they ought to have. In part, I say that through my own experience of research in looking at the debate around the role of the writer in the 1930s during the Great Depression. There were huge debates about what should writers do in this crisis. RC: Thatís a good point; let me rephrase the question. Whatís the role of a politically motivated writer, such as Upton Sinclair and those two or three other main writers that you talk about? Not writers in general. But what role could they play today? Iím not necessarily asking, ďWhat role should they play?Ē But Iím asking, What role can they play, in the context of the background I just gave you? WS: Itís important for people to be aware of them for a number of reasons, and to be aware of the ways that politics gets worked out through literature in this country: with all itís mistakes; with all its blind spots. Itís important for people to see how this process works and unfolds. And for people to understand that itís possible to be a writer and to be doing creative work, very creative work, and to still have political convictions, and to not see an incompatibility between them. John Reed, the famous writer whom Warren Beatty portrayed in the film Reds, was also very famous for one of the last statements he made, supposedly on his deathbed. He said, ďItís a hell of a thing, trying to juggle poetry and politics.Ē You know: the idea that revolution and poetry never go hand-in-hand.

The assumption that thereís an inherent conflict between poetry and politics is something that, for a long time, writers have dealt with or tried to work in the shadow of. I think itís important for writers, and for people today, students of literature, to understand thereís never been a huge conflict between creative work and political work. That the two have always gone hand-in-hand, going back to the eighteenth century even. And that you don't have to write an overtly political poem or novel for that to be a valid expression of your politics. So, right now, I see a lot of potential, particularly in poetry and politics. The reason I say that is because poetry Ė and this has always been true of poetry Ė has been an easier genre for people to make their lives heard in: for people who are not trained as writers to throw something together. For example, workers have often written poems. With the slam poetry movement that emerged about ten, fifteen years ago, that had, and still has, a lot of potential to be used for consciousness raising and for political awareness. Hip-hop has obviously gotten a lot of attention for its political potential. Talib Kweli, a contemporary hip-hop artist, was here a couple of nights ago as a guest, and he did some songs. It was obvious to everyone why he wanted to be here and why he wanted to perform for us. It was really profound, the kind of message he was providing. RC: You brought up an interesting point just now, about the fact that the two donít have to contradict each other. Jim Feast, whoís a critic for the Evergreen Review, has been doing an ongoing series about how the most significant writers are never writing out of a vacuum. Theyíre not just portraying themselves in a kind of cerebral cubicle, cut off from the rest of society. Instead, the really great writers are always mirroring or portraying something that, even through their individual actions, reflects the larger society, the major currents, the historical trend, the overall picture of the moment. Do you agree?

WS: I do, although I donít think theyíre always conscious of doing that. A very well known Marxist literary critic who teaches at Duke University, Fredric Jameson, wrote an influential book in the early 1980s called The Political Unconscious. His argument is that writers, whether they know it or not, are always responding to the political and social issues of their times. The work that theyíre doing is shaped by that, and itís always a response, whether itís conscious or unconscious. He used the analogy of dreams, Freudís theory of dreams, that our dreams are always a wish fulfillment. Jameson thought we should see literature as expressing a kind of wish fulfillment for some type of political solution or change in our society. I think thereís a lot to be said for that type of approach. RC: Of course, if dreams were wish fulfillment, weíd never have nightmares! But thatís a long discussion. WS: Freud actually has a lot to say about nightmares. RC: Heís got an excuse for everything, I know! WS: [Laughs] RC: What you said also reminds me of something else, which is that, on the opposite side of the spectrum that you just described, we also have cases where people like John Reed, for example, are so one-sidedly obsessed with the notion of changing the world, and obsessed with their political advocacy role, that sometimes we have to question whether there's something more personal at work thatís being projected upon this whole screen.

For example, in Reds, a marvelous film that touches on a lot of these things, Warren Beatty has several interviews with Henry Miller. And thereís a classic quote where Miller says: ďYeah, John Reed, he was a real rabble-rouser, a trouble-maker. The problem with him was that he wanted to change the world. And nobody can change the world, not even Jesus Christ. Look at what they did to him; they crucified the poor bastard!Ē Then he ends the quote by saying: ďWhen youíre that obsessed with wanting to change the world, we have to question whether thereís really something inside yourself that needs change.Ē A valid point? WS: Well, yes, thatís a valid point. But it doesnít invalidate the kinds of commitments and values that somebody like John Reed had, and the things he was trying to do. Thereís always a psychopathological or neurotic explanation for what everybody does. RC: Weíre motivated by many things Ö WS: Yes. RC: Most of them beyond the analysis of a Freud or a Jung anyway. WS: Yes. And apart from college debt, one thing that probably the majority of the people here have in common is that their mothers didnít love them enough! [Laughs] I mean, you could probably make that prediction. Or they had some other sort of familial issue that made them turn to issues of social justice and to see a lot of hope in that. But that doesnít discount or discredit the fact that theyíre still trying to do something positive, to make the world a better place to live. RC: Yes, indeed. Thanks so much for talking with me today. WS:

Thank you! *

In 1971, Johnny Got His Gun was made into a film that was directed by Dalton

Trumbo. It was remade in 2008 and directed by Rowan Joseph.

See also:

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Updated: July 2018 | All images and text Copyright © 2011 Rob Couteau |